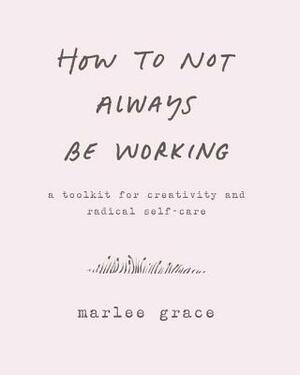

Title: How to Not Always Be Working: A Toolkit for Creativity and Radical Self-Care

Author: Marlee Grace

Genre: Self-Help

Trigger Warnings: Divorce (mention)

Back Cover:

Part workbook, part advice manual, part love letter, How to Not Always Be Working gently ventures into the liminal space where phone meets life, helping readers to define their work (aka what they do out of a sense of purpose), their job (aka what they do to make money), and their breaks (what they do to recharge, to keep sacred, to feel connected to themselves). The book delves into the discussion of what happens when your work and your job are connected or the same, and how to figure out how much is to much, and get the best use of your time.

For the corporate lawyer who is always on email as well as the bread-baker trying to something that’s just for themselves, How to Not Always Be Working includes practical suggestions such as getting a phone box and sleeping with your phone in a different room, and more philosophical prompts that invite readers to ask how they burn themselves out and why they’re doing it. A creative manifesto, this book is above all inclusive – insisting that deep breathing and yoga aren’t just for the 1 percent, and inviting any and everyone to create a scared space in their lives.

Review:

I don’t think the title of this book could have called to me any more if it was titled “Jay Needs To Read This Book.” I am generally always working. Most people assume it’s because I have three jobs. But though I do actually need two jobs to pay the bills, the third one is optional and voluntary. I have the time to not be working if I actually knew how to not always be working. I just have some sort of compulsion towards always doing something, and that something is almost always some variety of work.

I was so excited about the premise of this book that I actually paused when I got to the first exercise to do the exercise (which I’ve only ever done for one other book – generally I read books all the way through and then come back to any exercises). But that actually became the problem here. The first exercise was to write out a list of things that are your work. My list included items like “mending clothing,” “social media” (because, as one of my jobs is digital marketing, I’m hardly ever on social media if I’m not getting paid for it), and “most activities that happen in the kitchen.” Then I looked at the sample list Marlee provided, which included items like “balancing the books,” “posting on Instagram about a new product,” and “uploading a new podcast episode.” And realized that I had fundamentally misunderstood who this book is actually targeted at.

This book was not really written for people like me, who take extra jobs even though we don’t need them and who are always working because we have an undefinable, insatiable, irrational drive to always be “productive.” It’s targeted towards people who are self-employed in creative or hobby businesses or influencer-type gigs and who have a hard time drawing the lines between “I’m doing this for work because X is my job” and “I’m doing this for me because I enjoy X.” It is, fundamentally, about figuring out how and where to draw boundaries when your life and your hobbies are your work. (This is, obviously, not my situation. Besides reading, I don’t really have any hobbies. I was hoping this book would teach me how to change that.)

I’m sure this book would be valuable for people in that particular situation. I did finish it, and though it’s definitely influenced strongly by Marlee’s New Age-style witchy spirituality, a lot of the advice is very good and the exercises are practical. Honestly, I would probably find some of the exercises helpful anyway. But I haven’t done any besides the first one yet because I’m just so disillusioned with this book. I really love the principle and the idea and the concept and the call towards not always working. But I didn’t expect such a narrow focus on specific types of work. I probably will take the time to go back through the exercises and see what ideas I can extract and re-shape to fit my life. But sometimes you just don’t want to have to do that work, you know?